I owe the title of this piece to Natalie Wynn, whose YouTube channel ContraPoints is my latest obsession. In her video on beauty, she discusses the reasons she opted to have facial feminization surgery, which leads to a broader discussion of why women want to be beautiful, despite recognizing that “conventional beauty standards are a racist, sexist, ableist, fatphobic, transphobic social construct.” She may have added “ageist” to that list and does, in fact, later allude to it.

About fourteen minutes in, Wynn critiques the idea that women wear makeup to attract men by arguing that straight men don’t like makeup, or “at least they don’t think they do.” She supports this argument with a chart summarizing men’s responses to “no makeup,” “natural makeup” and “campy makeup.” In the case of “no makeup,” the opinion is that the person “looks diseased.” “Campy makeup” is considered “dumb.” “Natural makeup,” on the other hand, is interpreted as “no makeup” and clearly comes through as the most attractive option.

Here’s what’s insidious and downright infuriating about the results of Wynn’s survey: it suggests that what men consider attractive is not a truly natural face, but one made up to conform to a very narrow set of beauty standards while appearing convincingly natural. In my opinion, this is an important distinction with a dangerous fallout. What this means for women who feel compelled to conform to these standards, is that unless they’re indefinitely blessed with the complexion of a two-year-old, they must resort to artifice without seeming to do so. They must appear, in effect, to possess perfectly biological sequins. In practice, this may be achieved in a variety of ways, with “nude” makeup and plastic surgery representing either end of a very short spectrum of possible options.

Popular culture and personal experience confirm the results of Wynn’s survey. Those who still remember Desperate Housewives may recall the scene in Season 5, ep. 21 where Gabrielle “Gaby” Solis, played by Eva Longoria, reluctantly attends a high-profile event without makeup at her husband’s insistence, in order to teach her daughter Juanita the valuable moral lesson that it’s what’s on the inside that counts. “Don’t you love her enough to put your vanity aside for one night?” reproaches Carlos Solis, when his wife initially resists.

Over the course of the evening, Gaby feels compelled to reassure everyone from the valet to distinguished guests that she is not ill - she just isn’t wearing makeup. “I don't actually look this hideous,” she ensures them. When required to take a family photograph with the mayor for a newspaper, she finally snaps, steals another woman’s makeup bag, and reappears for the photo looking flawless and like her “true” self, disappointing her daughter.

To compensate for Gabrielle Solis’s moment of moral weakness, the episode ends with a saccharine and thoroughly unconvincing exchange between mother and daughter where, in answer to Juanita’s question as to when she will be allowed to wear makeup, Gaby replies, “you can wear makeup the day you realize you don’t really need it.” By all accounts, Juanita would still be barefaced in what would by this point be Season 17.

If makeup and skin care products prove insufficient in achieving the desired level of beautification, there are always peels, injections and Photoshop. The downside is that these treatments are expensive and require relatively frequent maintenance if you don’t want your jawline to start noticeably sagging like one of Dali’s clocks. Photoshop is difficult to pull off if you actually have to materialize somewhere. For a more permanent solution, there is always the scalpel.

We’re led to believe that plastic surgery - not (necessary and therefore virtuous) reconstructive surgery but (unnecessary and therefore shallow) cosmetic surgery - is a course of action infrequently resorted to, but numbers compiled by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons suggest otherwise. Of the 18.1 million procedures performed, over 13 million were injections, peels and laser treatments, and over 1 million were cosmetic surgical procedures including breast augmentation, eyelid surgery, facelifts, liposuction and nose reshaping.

A woman’s quest for beauty would feel less like it was lifted from a particularly grisly Greek myth if men had the appetite of a nineteenth-century aesthete for artifice. In J.-K. Huysmans’s 1884 “breviary of decadence,”2 À rebours, foppish, neurotic anti-hero des Esseintes has a tortoise’s shell encrusted with rare stones in order to improve on its insufficient natural allure. Contemplating his work with pleasure, des Esseintes finds that he’s grown hungry - a rare occurrence.

Huysmans’s text, along with many other examples of late-nineteenth-century literature, champions artifice over nature. The authors responsible for conveying such an outrageous idea were, however, identified as degenerates by their contemporaries, and relegated to the dark annals of infamy until a handful of scholars thought it might be fun to have another look at their work.3 An esteemed Victorian trope was, after all, the condemnation of vanity. Torchbearers of natural beauty and its analogous moral rectitude abounded then, as they do now.

If society openly acknowledged that the beauty standards it inflicts upon women require artifice in order to be achieved, and welcomed or even celebrated the public display of the mechanisms employed, at least women wouldn’t feel they had to skulk around patting the concealer out of their under eye cracks covertly or schedule fillers when their partners have gone fishing. They could brazenly lay out their foundations, moisturizers, serums, toners, shadows, pencils, blushes, highlighters, bronzers, lip stains, exfoliators, mascaras, illuminators, concealers, masks and glosses, and let all commend and admire their dexterity with a Mac no. 137 brush. Or they could strike up a frank conversation about cosmetic surgery over coffee.

Society, however, “pressures women to be beautiful while simultaneously belittling them for caring about it,” as Natalie Wynn points out. Makeup, when obvious, is pejoratively referred to as “fakeup,” plastic surgery meets with disapproval, criticism and even disgust. The denunciation of vanity is forever topical, which makes attaining the ideal all the more elusive. Equating the active pursuit of beauty through artifice with narcissism means women must resort to subterfuge in order to pass as beautiful while keeping up the appearance of virtuousness.

A fantastic scene from Season 1 of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, set in late-nineteen-fifties Manhattan, demonstrates the hoops the Mrs. jumps through in order to preserve the illusion of natural beauty. The scene shows Midge Maisel kissing her husband goodnight, wearing her day’s makeup and a frothy blue négligée. Once she’s sure he’s asleep, she jumps out of bed, washes her makeup off, applies a face mask, sets her hair in rollers, and slides back into bed beside him. Cut to the morning, and Mrs. Maisel is awakened by a slim ray of light let in by a strategically lifted blind. She jumps back out of bed, takes out the rollers, styles her hair, applies makeup, and crawls stealthily back into bed beside her still-sleeping husband, remembering to slide the blind back down. When Mr. Maisel is woken by an alarm clock, he is all smiles, and greets his beautiful wife with unquestioning, obvious pleasure. Midge pretends she has just woken up and hadn’t even heard the alarm. “You never do,” remarks her husband contentedly.

Mrs. Maisel may be fiction, and it may reference another time, but the bedtime beauty ritual feels decidedly real and current. The routine must be concealed as flawlessly as the bags under the eyes. Worse, those exposed to the illusion choose to suspend their disbelief in order to cogently succumb to the ruse, thus exonerating themselves from any part they may have played in its construction.

I’ve found that credence, however, is not limited to sex, gender or television scripts. There is almost a masochistic drive to compare oneself with a person identified as a paragon of natural beauty by those who uphold the ideal, particularly in a setting where the veracity of the “naturalness” may be reasonably questioned. It’s almost as though people take pleasure in belittling themselves.

As an example, I came across a makeup tutorial by Lisa Eldridge featuring Alexa Chung, widely recognized as a style and beauty icon. The video starts with Chung’s bare face, and then walks viewers through the steps to creating a Birkin-like sixties look. While there is a definite contrast between the initial and final looks, history, experience and indefinite hours on Instagram scouring the #bareface hashtag have taught us that faces and bodies on any visual platform are rarely completely devoid of makeup, or Facetune for that matter. Even those that are, which may be Alexa Chung’s case for all I know, benefit from studio lighting, clearly used in Eldridge’s video.

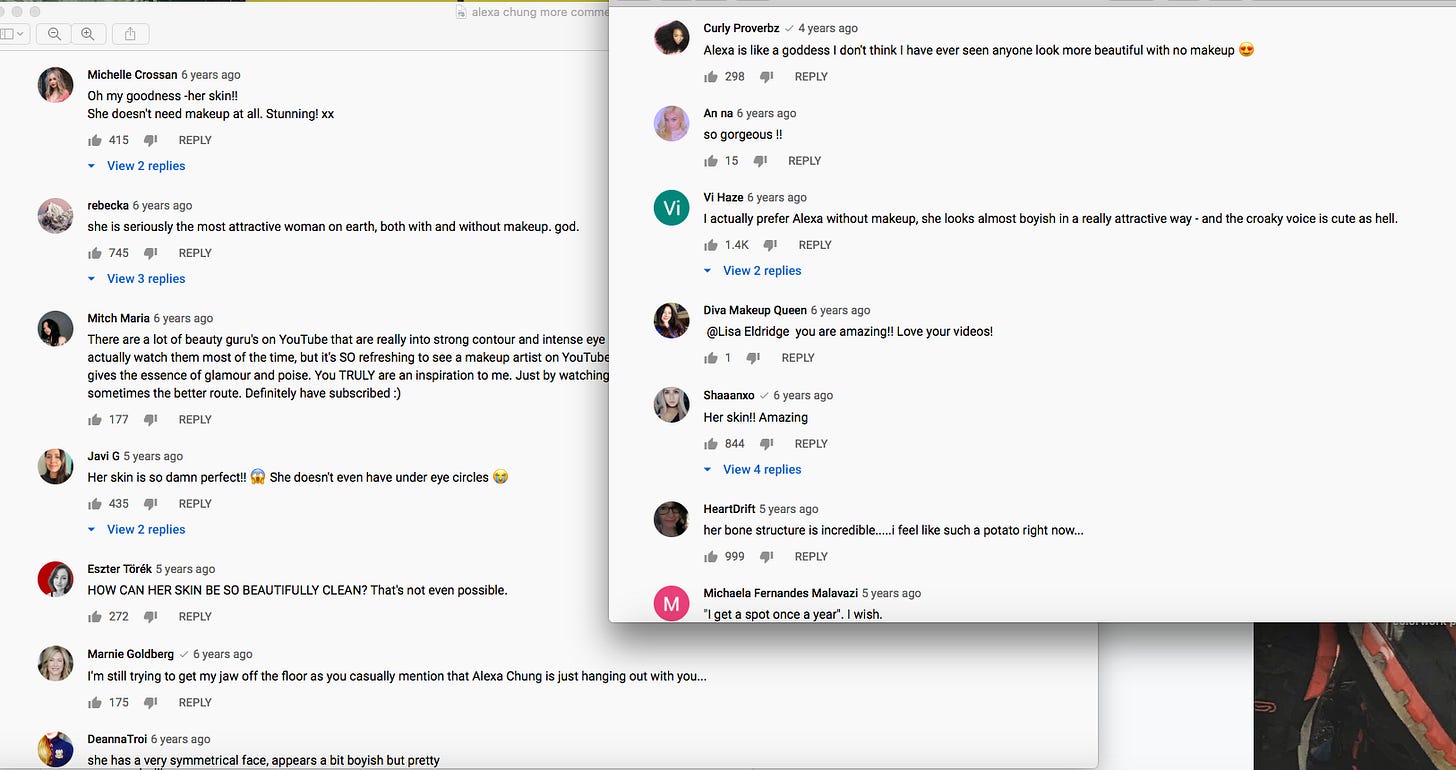

Most interesting, however, are the comments below the video. I’ve put together a sample of the large number that bewilderedly eulogize Chung’s naturally flawless skin, her facial symmetry and bone structure, all the while berating themselves or bemoaning the fact that they did not win that particularly genetic lottery. Exclamation marks abound. “I have never seen anyone look more beautiful with no makeup,” writes one viewer. “i feel,” writes another, “like such a potato right now...”

We know that video and photography necessarily involve some form of artifice, we know that “natural” beauty is often engineered, as overtly demonstrated by another tutorial of Lisa Eldridge’s entitled My Ultimate “Secret” Makeup Look. Yet we still willingly believe, internalize and castigate ourselves into conforming to unrealistic natural beauty standards. Which leaves us waiting like a bunch of seedy muck rakes for a bad paparazzi photo to alleviate our anxiety for about five minutes.

What’s the term for the internalization of unrealistic perceived beauty ideals to the point where it becomes pathological, again? Can’t we just transfer all that elusive youth, symmetry and perfection back onto Polyclitus’s Canon for heaven’s sake?

Recourse to artifice is condemned. Absence of artifice is also condemned. Either the soul or the skin is perceived as diseased. By this point, we know what options are left for those who can’t shut out the siren’s song of conformity.4

I may not presently be offering any viable solutions to an insidious problem, but I can tell you that it feels good to get this off my chest. While I’m at it, maybe we could just lift my chest an inch or two towards my neck.

I’m finding Dali’s clocks to be an extremely versatile metaphor. I can’t promise they’ll make an appearance in every newsletter, but two in a row ain’t bad.

Huysmans’s À rebours was described as the breviary of decadence by his contemporary, British poet and critic Arthur Symons.

One of the most amusing quotes from the period is Margaret Armour’s appalled reception of the work of fin-de-siècle decadent French authors and artists, including Verlaine and Degas. In the Magazine of Art, she warns of the “tainted whiffs from across the channel which lodge the Gallic germs in our lungs.” Let it be noted that the art and literature of the degenerate is treated like a dangerous, highly contagious disease. Find the full article here.

In case it wasn’t clear, I one hundred percent include myself in those who have thrown themselves to sea.